Morrill’s Handsome homage to the square

By Bill Homisak

Art Critic: The Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, October 13, 1989.

Painter Michael Morrill has spent the last 15 months "moving away from the hard edge."

By hard edge, the artist is referring to the meticulously painted, autocratic pinstripes that have brought order to his abstract canvases over the last five years or so. Now these razor-sharp lines, laid down with the aid of masking tape, are giving way to bigger areas of paint that look as though they are — in Morrill's term — "eroding."

"I guess you could say I'm fusing geometric abstraction with action or gestural painting," explains the 37-year-old Pittsburgh artist. "But the gestural aspect of my new painting is related to gravity rather than ‘inner angst.’”

(By gravity, Morrill means the same force of nature that caused Pollock's drip paintings to drip, or Morris Louis' color 'veils' to flow.)

Morrill's remarks are occasioned by his exhibit of stunning new paintings at Pittburgh's Concept Gallery. It would be wrong to say Morrill's work no longer bears a characteristic strictness. These are still clean-cut pictures. But this strictness goes hand-in-hand with a sense of repose uncommon in today's art.

I used to think Morrill's canvases boring; I don't anymore.

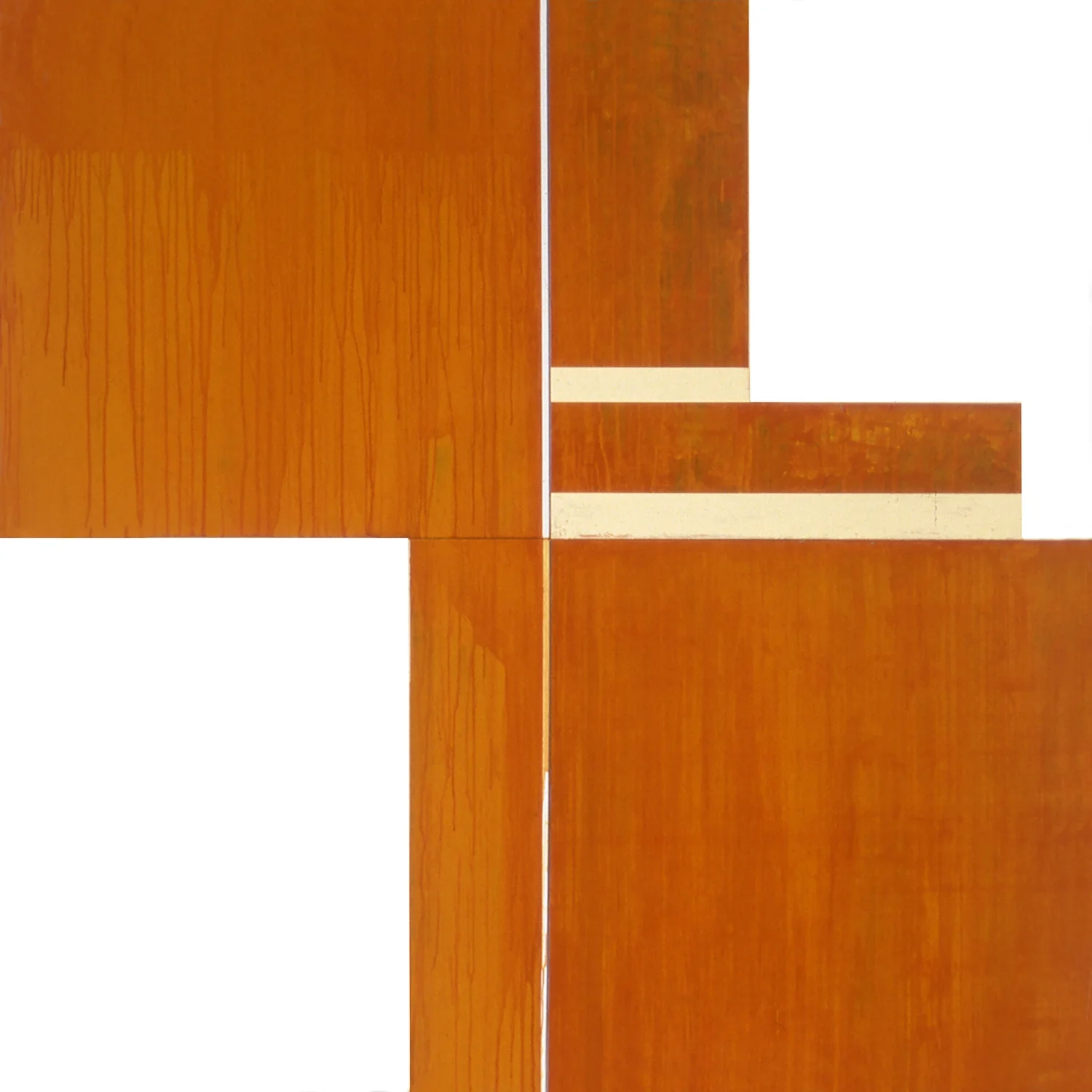

Despite Morrill’s search for a looser approach to his work - a thawing, if you - will he still wants to “retain control”. His “Divided Square” paintings, of which there are 59 in the series to date, are painterly gridlocks - orthogonal essays in starts and stops, scrapes and pulls, thick and thin running paint. These are intensely labored canvases comprised of countless layers of underpainting. They give the impression of constant refinement.

The gray-green acrylic paint on "Divided Square No. 46", for instance, has been finessed and manipulated to the point where it looks like Italian marbleized paper. On the other hand, "Divided Square No. 58”, is awash with the vicissitudes of lush pumpkin-red like a mud — or rather, color — slide.

And Morrill's subtle technique causes the blue-black surface of "Divided Square No. 50" to shimmer like silk moiré.

"Abstraction is still the big idea of the 20th century," says Morrill. “But the issue is to infuse abstraction with meaning and significance beyond abstract form itself. Abstract painting today is like splitting hairs. You can't avoid making reference to work that has already been done.”

The seductive order of the square, the compositional basis of Morrill's paintings, may have been instilled in the artist as a child. A native of Vermont who grew up in Connecticut, Morrill was no stranger to the classical geometry of American Colonial church architecture.

But his artistic influences are as far-ranging as the Russian cubist Kasimir Malevich and the father of neo-Plasticism, Piet Mondrian. ("I love Mondrian's slow dissolve from representation into abstraction,” Morrill says.) And while it may come as a surprise to those familiar with his work, Morrill is also attracted to the luminous light of the American 19th-century landscape painter, Frederick Church.

Morrill, an associate professor of art at the University of Pittsburgh, was included in the “10 Americans”, the 1988 survey of contemporary abstraction at The Carnegie Museum of Art, curated by John Caldwell.

Morrill has also shown in New York, and his work is represented in the collection of The Carnegie. As an undergraduate at Alfred University in New York, Morrill studied ceramics. He entered graduate school at Yale as a sculptor.

Doing a complete about-face, Morrill turned from sculpture to painting six years ago. And while there is a strong physical component to his shaped canvases, Morrill prefers to call what he does “painting”.

(Concept Art Gallery, 1031 S Braddock Ave, Pittsburgh, PA, October, 1989)